Lately, I've had many conversations about zero-waste pattern design, so I thought I'd lay out the mathematics behind it. Let's begin with the first part of the problem: optimizing fabric usage given a fixed set of pattern pieces.

Summary: This article explores the mathematical optimization problem at the heart of zero-waste fashion design and AI-powered marker making. Marker making—the process of arranging pattern pieces on fabric to minimize waste—is a classic optimization problem that suffers from the curse of dimensionality. LA VIPÈRE uses advanced algorithms including simulated annealing, genetic algorithms, and AI-based methods to solve this problem efficiently. The article covers the mathematical formulation (objective function, variables, constraints), explains why brute-force approaches are computationally infeasible, and details how AI can shift computational cost to the training phase for instant inference. Beyond optimizing fixed patterns, the article discusses how AI enables the generation of inherently zero-waste patterns by design.

Why Zero-Waste Pattern Optimization Matters

The Scale of Fabric Waste: The fashion industry generates approximately 15% fabric waste during the cutting process alone. For large-scale production, this represents millions of dollars in wasted materials and significant environmental impact. Even a 5% improvement in fabric utilization can save substantial resources across the supply chain.

Economic Impact: Fabric typically represents 40-60% of garment production costs. Better marker making directly impacts profit margins, especially for manufacturers producing thousands of units where even small efficiency gains compound dramatically.

Computational Complexity: The marker making optimization problem is NP-hard, meaning there's no known algorithm that can find the optimal solution in polynomial time as the number of pieces grows. This is why AI and approximation algorithms are necessary.

Beyond Cost Savings: Reduced fabric waste means lower environmental footprint, less textile waste in landfills, and more sustainable fashion production. This aligns with growing consumer demand for sustainable practices.

The Fabric Waste Problem

The fashion industry faces a massive fabric waste challenge. During garment production, pattern pieces must be arranged on fabric rolls—a process called marker making. Poor arrangements lead to significant fabric waste, with industry averages ranging from 15-25% material loss.

This isn't just an environmental issue—it's an economic one. Fabric represents the largest cost in garment production, and every percentage point of waste reduction directly impacts profitability. For a manufacturer producing 100,000 units, even a 2% improvement in fabric utilization can save hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The Mathematical Formulation

As suggested, marker making is a classic mathematical optimization problem. To formulate it properly, we need three core components:

1. Objective Function

In our case, this is the total area of fabric consumed. The goal is to minimize this area. Mathematically:

Minimize: Total Fabric Area = Width × Length

Where the fabric length is determined by the furthest extent of any pattern piece after arrangement.

2. Variables (Degrees of Freedom)

These include the position, rotation, and flipping of each piece. Each pattern piece contributes a 6-dimensional vector:

- 2 for displacement (x, y position on fabric)

- 2 for rotation (angle, considering fabric grain restrictions)

- 2 for flipping (horizontal and vertical mirroring possibilities)

For a garment with 20 pattern pieces, this results in a 120-dimensional optimization space. The complexity grows exponentially with each additional piece.

3. Constraints

Real-world marker making must satisfy multiple constraints:

- No overlap: Pattern pieces cannot intersect. This requires collision detection, often optimized using hierarchical spatial trees (quadtrees, R-trees) to reduce computational checks from O(n²) to O(n log n).

- Grainline alignment: Many pieces must follow the fabric's grainline for structural integrity and drape. Some pieces allow diagonal placement (bias cut), while budget production may drop this constraint entirely to save fabric.

- Flipping rules: Asymmetric pieces with specific right/left designations cannot be flipped. Symmetric pieces offer more placement flexibility.

- Fabric width: All pieces must fit within the fixed width of the fabric roll.

- Pattern matching: For striped or patterned fabrics, pieces must align at seams.

Why Brute Force Doesn't Work

The naïve approach would be to try every valid arrangement, calculate the fabric usage, and select the layout with minimum area. But this would take forever to compute. And I don't mean that metaphorically.

Optimization tasks suffer from a problem called the curse of dimensionality. Even though the problem seems straightforward (it's just an area calculation), finding the optimal solution becomes exponentially difficult with the number of pieces added to the system.

The Numbers

Consider a simple garment with 10 pattern pieces:

- Each piece can be positioned at ~1000 discrete positions (conservative estimate)

- Each piece can have ~360 rotation angles

- Each piece can be flipped or not flipped (2 states)

This gives approximately (1000 × 360 × 2)^10 ≈ 10^65 possible arrangements. Even if we could evaluate one billion arrangements per second, we'd need longer than the age of the universe to check them all.

This is why we resort to approximation algorithms. These don't guarantee the absolute best solution, but they find a good enough solution in reasonable time. The trade-off is between solution quality and runtime.

Optimization Approaches

Simulated Annealing

Inspired by the physical process of annealing in metallurgy, this technique treats each layout as an energy state. The algorithm:

- Starts with a random arrangement (high energy state)

- Randomly perturbs piece positions (explores neighboring states)

- Accepts improvements immediately

- Sometimes accepts worse solutions (controlled by a "temperature" parameter)

- Gradually reduces temperature, settling into a stable, near-optimal configuration

The occasional acceptance of worse solutions prevents getting stuck in local minima—similar to how heating metal allows atoms to escape local energy wells and find better global configurations.

Technical Detail: The acceptance probability for worse solutions follows the Boltzmann distribution: P = exp(-ΔE/T), where ΔE is the energy increase and T is the current temperature. This creates a probabilistic hill-climbing mechanism that becomes more conservative as temperature decreases.

Genetic Algorithms

These mimic natural selection, evolving better solutions over generations based on fitness criteria. They literally simulate the survival of the fittest concept:

- Initial population: Generate random marker arrangements (genomes)

- Fitness evaluation: Score each arrangement by fabric utilization

- Selection: Choose the best performers to "reproduce"

- Crossover: Combine features from two parent arrangements

- Mutation: Randomly modify some piece placements

- Repeat: Iterate for multiple generations

Over time, beneficial "genes" (good placement strategies) propagate through the population while poor strategies die out. This parallel exploration of the solution space often finds better results than sequential methods.

AI-Based Methods

This is where LA VIPÈRE's approach becomes particularly powerful. While simulated annealing and genetic algorithms incur similar computational costs every time you run them, AI can shift that cost to the training phase.

Once trained, a neural network can instantly generate optimal or near-optimal layouts. Inference is fast—often milliseconds instead of minutes—and the heavy lifting is done only once during training.

How AI Learns Marker Making

Our geometric AI learns marker making through:

- Pattern recognition: Understanding common piece shapes and their optimal placement strategies

- Spatial reasoning: Learning geometric relationships between pieces

- Constraint satisfaction: Internalizing rules about overlap, grainlines, and fabric width

- Iterative refinement: Learning from millions of marker examples to recognize efficiency patterns

The AI develops intuition about which pieces naturally nest together, which orientations save space, and how to balance competing constraints. This knowledge transfers across different garments—insights learned from optimizing shirt markers help with dress markers.

Beyond Optimization: Generative Zero-Waste Design

Here's where the problem becomes even more interesting: What if we could design patterns that are inherently zero-waste from the start?

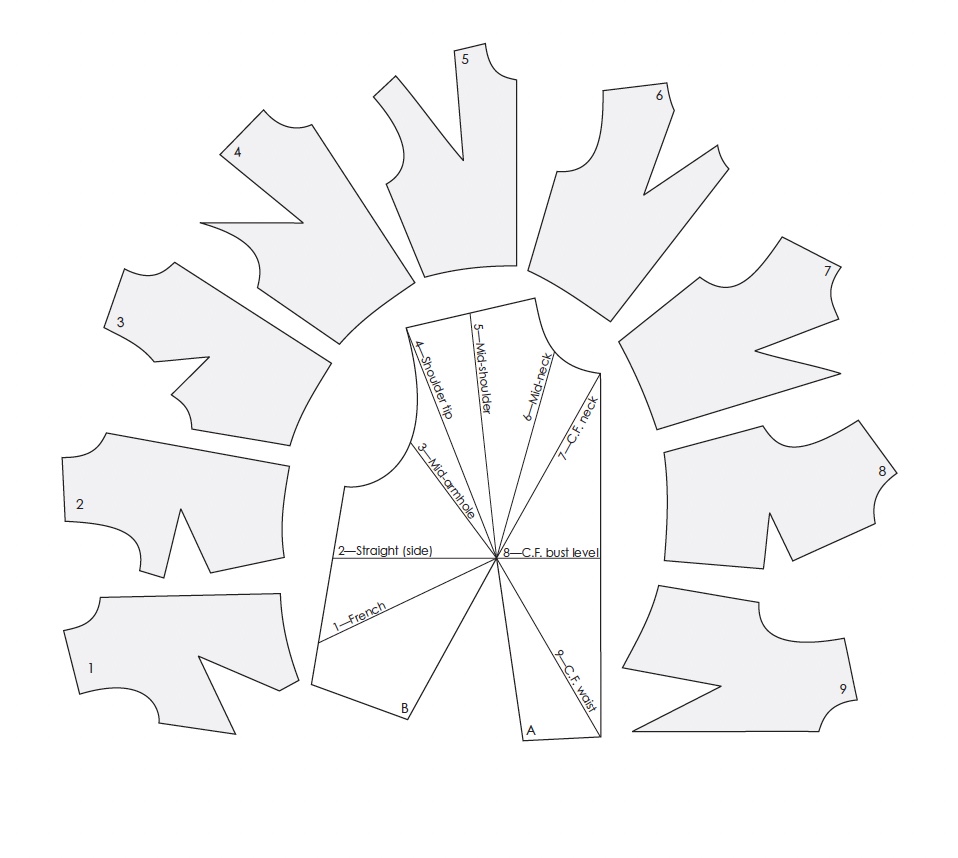

Traditional marker making optimizes fixed pattern pieces. But when we move from optimizing fixed patterns to generating patterns that are inherently zero-waste by design, AI becomes the only scalable solution.

The Paradigm Shift

Instead of:

- Design garment → Create patterns → Optimize marker → Accept waste

We can now:

- Design garment → Generate zero-waste patterns simultaneously → No waste by construction

How Generative Zero-Waste Works

This requires the AI to solve an inverse problem:

- Input: Desired garment design and aesthetic

- Constraint: All pattern pieces must tessellate perfectly on fabric (zero waste)

- Output: Pattern pieces that achieve the design while fitting together like a jigsaw puzzle

This is exponentially more complex than traditional marker making because the AI must simultaneously:

- Ensure proper garment fit and drape

- Maintain design aesthetics and proportions

- Generate geometrically valid, sewable patterns

- Guarantee zero waste through perfect tessellation

Only geometric AI with deep understanding of both garment engineering and spatial optimization can solve this multi-objective problem in real-time.

Zero-Waste Design in Practice

The zero-waste design movement has been growing, with designers and researchers pioneering techniques for eliminating fabric waste. Notable resources include:

- Redress Design Award's Zero-waste Guide - comprehensive guide to integrated zero-waste design processes where designing and sourcing go hand in hand

- Dr. Mark Liu's Zero-Waste Fashion - academic research on designing out waste from the beginning of the process

- Svegea's Zero Waste Pattern Cutting - exploring zero-waste as a revolution in sustainable fashion design

- GOLDFINCH Textile Studio - practical insights on zero-waste pattern drafting and cutting from the beginning stages

- The Craft of Clothes - hands-on tutorials for making zero-waste patterns

- Dinesh Exports - zero-waste pattern making techniques for sustainable fashion manufacturing

- Selkie's Zero-Waste Approach - visual guide to sustainable cutting techniques

While these manual approaches require significant expertise and time, AI can automate and democratize zero-waste design, making it accessible at scale.

Real-World Impact

Manufacturing Scale

For a mid-size manufacturer producing 50,000 garments per month:

- 5% fabric reduction = $50,000-100,000 monthly savings

- 10% fabric reduction = $100,000-200,000 monthly savings

- Annual savings can reach millions of dollars

Environmental Impact

Reducing fabric waste by 10% for a medium-sized brand means:

- Tons of textile waste diverted from landfills annually

- Reduced water consumption in fabric production

- Lower carbon footprint from decreased material processing

- Smaller dye and chemical usage

Speed to Production

Traditional marker making by experienced professionals:

- Simple garment: 30-60 minutes

- Complex garment: 2-4 hours

- Multiple size grading: Additional hours per size

AI-powered marker making:

- Any garment: Seconds to minutes

- All sizes simultaneously optimized

- Instant iteration on design changes

The Future of Sustainable Fashion Production

AI-powered marker making represents a fundamental shift in how we approach sustainable fashion:

Immediate Benefits

- Democratized expertise: Small brands gain access to optimization previously available only to large manufacturers with dedicated marker-making teams

- Real-time adaptation: Instant marker optimization as designs evolve, enabling faster iteration

- Consistent quality: Every marker achieves near-optimal efficiency, eliminating human variability

Long-Term Transformation

- Zero-waste becomes the default: As generative zero-waste design becomes computationally feasible, it will shift from niche practice to industry standard

- On-demand production optimization: Each custom order gets individually optimized markers, making personalized fashion sustainable

- Circular fashion enabling: Better fabric utilization makes small-batch and circular production economically viable

- Knowledge democratization: Marker-making expertise, previously gatekept behind years of experience, becomes accessible to emerging designers

Building Sustainable Fashion Through Mathematics

The mathematics of zero-waste pattern design reveal a deeper truth: sustainability and profitability are not opposing forces. They're two sides of the same optimization problem.

By minimizing fabric waste, we simultaneously reduce environmental impact and production costs. By making this optimization accessible through AI, we enable sustainable practices at every scale—from independent designers to global manufacturers.

At LA VIPÈRE, we're not just building pattern-making software. We're building the mathematical infrastructure for sustainable fashion production. Every garment designed on our platform benefits from decades of optimization research, computational geometry advances, and AI innovations—all working together to make fashion more efficient, more sustainable, and more accessible.

This is how we use mathematics to reshape an industry.